We are excited to announce that Issue 2 of RAMBLE is now live! This issue features poetry, prose, and photographs by Georgia Tech students of diverse cultural and academic backgrounds. Our authors write of the infiniteness of nature and of human smallness; of the comforts of mother tongues and grandmothers’ food; of the beauty of multilingualism but also of the at-times fraught relationship between language and identity, and of systemic issues of language and power. We hope that you enjoy their work as much as we do. If you’d like to learn more about RAMBLE, you can read about us here and check out Issue 1 as well.

Month: April 2021

World Cinema Spotlight: The Tale of Princess Kaguya

Title: The Tale of Princess Kaguya [かぐや姫の物語 (Kaguya-hime no monogatari)

Director: Isao Takahata

Released: 2013

Country: Japan

Language: Japanese

English Subtitles: Yes

Closed Captioning: Yes

Streaming/Available on: HBO Max; Amazon Prime Video (Japanese audio with English subtitles and English audio versions both available)

Up next for the World Englishes Committee’s World Cinema Spotlight is The Tale of Princess Kaguya, かぐやの物語 (kaguya no monogatari), a Studio Ghibli film directed by Isao Takahata. While Studio Ghibli is perhaps best known for Hayao Miyazaki’s international hits such as Princess Mononoke, My Neighbor Totoro, and Spirited Away, Takahata’s Kaguya holds its own, from the plotline to the artistry and the soundtrack. The story is based on an ancient Japanese legend known as “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter,” 竹取物語 (taketori monogatari). The legend dates as far back to the Heian period of Japan in the 10th century, and in fact is one of the oldest written monogatari, or fictional tales. In the legend, an old bamboo cutter discovers a Thumbelina-esque princess inside a bamboo shoot; he and his wife then decide to raise her as their own daughter. While the basic plot is the same between the original monogatari and the film adaptation, the film adds additional social context for its titular character, Kaguya, by giving her a group of similarly-aged friends at the beginning of the movie. While a story based on a folk tale might sound simplistic, Kaguya pulls a great deal of emotional weight, grappling with sophisticated themes such as the transience of nature and life; the conflict between our conscious and unconscious desires; and the bonds between parents and children. Aesthetically, the film is a powerhouse, its style evoking that of traditional Japanese scroll work and ukiyo or “floating world” paintings.

[Warning: Skip the next paragraph if you want to avoid plot spoilers!]

At the beginning of the film, a bamboo cutter finds a beautiful miniature princess in a magically growing shoot of bamboo. When he takes her home, she transforms into a baby that he and his wife raise as their own. The princess, known as Little Bamboo Shoot because of the speed of her growth, loves her life in the country among birds, bugs, and beasts. She especially befriends a young man named Sutemaru. However, after finding increasingly lavish gifts in the bamboo grove, such as gold and noble robes, the bamboo cutter commits to moving the family to the capital and bringing up Little Bamboo Shoot as a princess–the Princess Kaguya. She bristles at the impositions of noble femininity, especially as she must contend with the unwanted advances of the most eligible suitors in the land–court advisors and ultimately the Emperor. In a moment of panic, when surprised and embraced by the Emperor, she wishes for escape, and the people of the Moon–Kaguya’s original home–come to take her back, even though she wants to stay on Earth with her parents and, maybe, Sutemaru. Despite the defense that her parents set up and contrary to Kaguya’s express wishes, the moon people fly in on a cloud, erase Kaguya’s memories of Earth with a magical robe, and take her back. In the movie’s final moments, Kaguya takes one last look back at Earth with tears in her eyes.

Recently, World Englishes committee members Eric Lewis and Kendra Slayton sat down for a discussion of the film. You can listen to our conversation here (skip the plot summary from 1:30 to 3:10 in the recording to avoid spoilers, though we discuss film details throughout):

“Polygluttony” at Duolingo’s Language Buffet

Introduction

When my mother-in-law comes to visit, once a day she pulls her phone out and says something like, “Time for Spanish!” Using the Duolingo app, she has been learning and practicing Spanish for some time. She has even built up a couple of impressive consecutive-days streaks numbering in the hundreds (meaning consecutive days meeting her specific daily language goals on Duolingo). When I acquired a smartphone, I too downloaded the Duolingo app because I wanted to begin studying German again. I received a minor in German in 2010 when I graduated with my B.A., but it has been a long while since I studied the language in a structured way.

I wanted to test out my first impression of Duolingo (the one I formed unfairly, of course before ever trying it out) as a language learning buffet by taking lessons in each of the languages it offers. This article is a reflection on my perceptions of the Duolingo app and my user-experience, as well as an evaluation of Duolingo’s functionality as a tool for language learning. Each day for just over a month I downloaded a different course and tried it out, journaling my impressions along the way. With some, I already had a level of proficiency, so I took the diagnostic test to see where Duolingo thought I was. With others, I knew absolutely nothing, so I started from square zero, also known as the “New to __________?” button. I am not seeking fluency in any of these languages because frankly I see that as an impossible goal to achieve in Duolingo anyway, even if I were to focus solely on a single course. It was more of a fun way to experience what it is like to be “Hgf” (username) on my Duolingo leader board, who has downloaded the Italian, Russian, Portuguese, Chinese, Spanish, and French courses. I am simply doing what that learner has done and taking it to an extreme.

Note: The slides embedded throughout this article are an account of my experiment taking lessons in a different language every day for just over a month. If you just read the journal, the slides will auto-advance. If you finish reading a slide before it advances, use the controls in the taskbar at the bottom of the frame to skip ahead.

Background

Using Duolingo, language learners, like my mother-in-law, can select any of a range of “standard,” endangered, or even constructed languages to study:

| Spanish

French German Italian English Japanese Chinese Russian Korean Portuguese Dutch |

Swedish

Norwegian Turkish Polish Irish Greek Hebrew Danish Hindi Czech Esperanto |

Ukrainian

Welsh Vietnamese Hungarian Swahili Romanian Indonesian Hawaiian Navajo Klingon High Valyrian |

According to its website, Duolingo collects data from language learners to discover how they learn language best. The Duolingo team claims, “With more than 300 million learners, Duolingo has the world’s largest collection of language-learning data at its fingertips. This allows us to build unique systems and uncover new insights about the nature of language and learning” (“Research”). Duolingo makes multiple publications about their approach to second-language learning on their website, as well as a favorable study conducted by researchers from the University of South Carolina and the City University of New York.

Every large-scale language-learning program requires a theoretical framework. The Duolingo system reflects at least in part the ideas of Stephen Krashen, whose input hypothesis, despite having received some criticism, has influenced many language learning programs in the U.S. today. To scaffold language-learning, Duolingo provides linguistic input in “the Four Skills”: reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Comprehensible input is language input around the learner’s proficiency level but involves what Krashen calls “i + 1” (Ellis 47). The phrase i + 1 refers to input that introduces new linguistic principles that students are primed to receive. I like to think of i + 1 in terms of Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

- “This porridge is too hot!” = i + 2-∞, meaning input that is so far beyond the learner’s proficiency level that it is essentially incomprehensible.

- “This porridge is too cold!” = i (or i + 0, if you prefer), meaning input consisting only of what a learner already knows. These principles might be good to practice, but they also might become boring, and without the introduction of new material might lead to stagnation.

- “This porridge is just right!” = i + 1, meaning comprehensible input or input that merges new content with enough known content that students can progress in the target language. Comprehensible input in the right kind of environment leads to language acquisition and the production of comprehensible output (output in the target language that makes sense to others) (Krashen 409).

The app approximates a learner’s proficiency level or i at the beginning of each course by providing a diagnostic test. If the learner already has some proficiency of which they are aware, they can click the button marked “Already Know Some __________? Try this Placement Test.” If not, the learner can click the “New to __________?” button and begin learning some basic vocabulary with the help of cues such as capital letters or even images. Those basic terms become keys to help students decipher input in the target language.

Trying the App

In my first lesson in Welsh, of which I previously knew nothing, I was presented with Bore da as my first sample of Welsh. I also received a number of multiple-choice answers to select from. Two of the possible answers were names: “Megan” and “Morgan”; two of them were capitalized: “Good” and “Goodbye”; and two of them were not capitalized: “good” and “morning.” Logically, I eliminate “Megan” and “Morgan” right off the bat (nothing personal), mainly because of their lack of lexical usefulness. Why would I need to know their names in Welsh? The target phrase was capitalized, so I kept “Good” and “Goodbye” and discarded “good” because the capital letter makes “Good” seems more likely than “good.” Bore da is also two words, so I decide on a two-word answer in English: “Good morning.” Choosing a two-word translation in the L1 for a two-word phrase in the target language is one instance of linguistic transfer, a common strategy employed by language learners to fill in gaps in their communicative competence. In this case, I have chosen correctly, even though I still do not know which Welsh word is “Good” and which is “morning.” Also, for all I knew, “Goodbye” in Welsh is also two words.

The lesson later asks me the meaning of da and provides multiple choices that include “good,” but not “morning.” I know that had I not received the capitalization cues in that first sample, I probably would have leaned on the syntax of my L1 and answered incorrectly because Bore da would be literally translated as “morning good” in English. Scaffolding cues like capitalization or images can matter greatly in helping beginning students puzzle out their first few steps into another language. Any program needs to know where a student’s proficiency level is before it can meet them where they are and guide them beyond it. In language learning, that is the true value of i.

Skepticism

As a brand-new Duolingo user, I had a hard time appreciating the app as a serious tool for language learning, despite its theoretical basis in SLA theory. I perceived it as more like a buffet for language learners in which we can choose one thing or choose some of all of our favorites. We can pile our plates with Polish and Chinese and Spanish and Hawaiian and High Valyrian, if they suit us. We aspiring polyglots (or maybe “polygluttons” is a more applicable term) can cram ourselves with little bits of a lot of different things, which is perfect if we are not interested in acquiring fluency but rather knowing more about individual languages and learning a few words and key phrases in each.

Language Journal

Conclusions

As a result of my exploration of the app, my impression of Duolingo as a language buffet remains unchanged. However, I do appreciate what it is trying to do with the technological affordances it has available. The system is impressive in the way it turns language learning into a game using rewards, fake currency, leader boards to promote competition, and leagues. It promotes engagement and provides learners with structure. It gives plenty of input, fortifies grammatical and lexical knowledge, and provides plenty of opportunities to practice reading and writing, though not nearly as much as it could listening and speaking. Overall, Duolingo is certainly making good on its endeavor to make learning engaging (“Our mission is to make learning free and fun,” says the app).

The game aspect provides plenty of extrinsic motivation for learners who need an additional push to study. Learners might lean toward either extrinsic (I want to learn a language because it is cool!) or intrinsic (“I want to learn a language because it will do something for me or promises a reward!”), but most learners need both to learn a language. I want to learn languages because I am interested in languages, but there were days when I had far less of a desire to study. However, I did not want to fall into the “Demotion Zone” (which is the bottom five on my leader board) because then I would fall into a lower league. I am currently in the Sapphire League, thank you very much, and I am not going back to the Gold League. That leader board gave me the push I needed to study.

That being said, there are a number of people using the app who find the game aspect unsustainably fulfilling. After a while, the motivation derived from that part of the game can ebb away. Another aspect that Duolingo learners complain about is that some people are in it more for the game than the language, and so search for shortcuts to make more points or “XP,” as the game calls them. When the student’s focus turns away from language learning toward a secondary feature, the app becomes less successful at what it ought to be doing.

All things considered, I am not buying Duolingo’s other claim about its mission, namely, “To develop the best education in the world and make it universally available” (“Crown Levels: A Royal Redesign”). I believe they want this, and based on the number of people using the app, I would say that they are certainly reaching toward the “universal availability” objective. But it doesn’t offer the “best education” yet, and it likely never will unless we come up with a quantifiable standard to define what it means to be “best.” Like any other language program, Duolingo has limitations. No one should download and use the Duolingo app without first understanding that it is not THE WAY to learn a language because there is no such thing, as Dr. Brent Wolter pointed out in a 2019 interview (“TESOL”). That being said, Duolingo provides opportunities for prospective learners to increase their communicative competence in a target language within a low-stakes and gamified environment that can motivate learners who are motivated either intrinsically or extrinsically.

Using Duolingo as the sole source of one’s language learning will only set a learner up for disappointment if they think they can use it to achieve native-like proficiency in the “Four Skills.” Duolingo is probably best used as a language learning supplement that activates your brain during your early commute on the train as you puzzle out the difference between the Turkish words adam and erkek or the Portuguese words copo and xicara. Prospective users of this app would be well served if they would keep, as I do, a dictionary and a good grammar book about the target language on hand, and find friends to consult and converse with in that language as well.

Note: As a final note to educators, I can say that trying out the Duolingo app could be a useful experience. If you want a quick way to learn a little bit about the languages your students speak without having to commit yourself to a full-blown language course, Duolingo might be the way to go. My Georgia Tech students come from many different countries and speak languages I do not know, including Chinese, Turkish, Tamil, etc. Having tried to learn a little bit of some of those languages and felt the frustration that comes from attempting to learn a language so dissimilar from my L1, I feel greater empathy for their endeavors to learn English. In fact, any opportunity teachers or tutors can get to know the first languages of those they teach a bit better, the better off those teachers will be. I believe language, linguistics, and ESL teachers would be well-served to find some language-learning program (if not Duolingo, then something else that might be affordable and effective, if not “free and fun”). They can try out some of the lessons and see if it influences their linguistic awareness, as well as their attitudes toward the English learners in their classes.

Addendum: Since this article, Duolingo has made a few updates, one of which is especially noteworthy. In the summer of 2019, Duolingo released an Arabic for English speakers course. I made a note of the absence of such a course in my journal entry on Swahili, finding it strange that such a significant language would not be represented in the app. Duolingo has also continued to develop other language courses, including Finnish, Scottish Gaelic, and Yiddish.

Works Cited

Duolingo. “Research.” Duolingo, n.d., https://ai.duolingo.com/. Accessed 25 Mar. 2019.

Ellis, Rod. Second Language Acquisition. Oxford University Press, 1997.

Krashen, Stephen. “The Input Hypothesis: An Update.” Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics (GURT) 1991: Linguistics and Language Pedagogy: The State of the Art. Georgetown University Press, 1992. Google Books, https://books.google.com/books?id=GzgWsZDlVo0C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false. Accessed 27 Mar. 2019.

Rollinson, Joseph. “Crown Levels: A Royal Redesign.” Duolingo, 11 July 2018, https://making.duolingo.com/crown-levels-a-royal-redesign.

Wolter, Brent. “Dr. Brent Wolter on Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL).” World Englishes, Georgia Institute of Technology, 13 Mar. 2019, https://worldenglishes.lmc.gatech.edu/interview-dr-brent-wolter-on-tesol/. Accessed 27 April 2019.

This article appeared on our site in 2019 and is now being republished here as part of a website makeover. ~ Jeff Howard

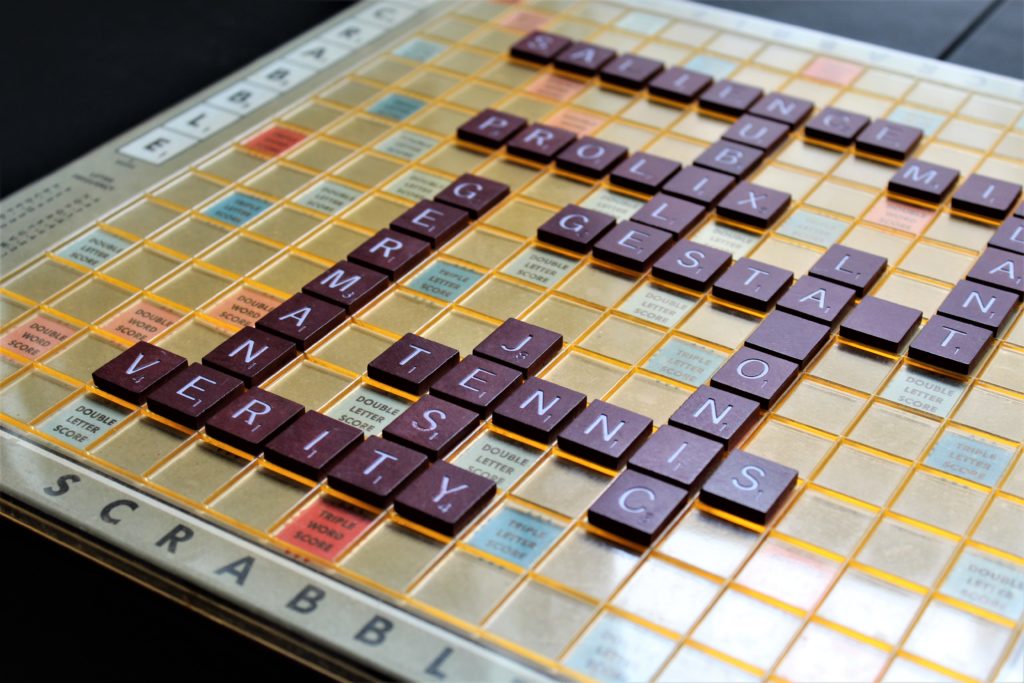

“Infinite Jest and Sesquipadalia: Reading for (Scrabble) Vocabulary”

I recently finished reading David Foster Wallace’s book Infinite Jest (1996), and I am exhausted. It seemed that every page I read on average contained some word I could not define, even using context clues. Ryan Compton estimates that “Wallace used a vocabulary of 20,584 words to write Infinite Jest.” This vast vocabulary contains jargon, archaisms, neologisms, and all-around sesquipedalia—long, polysyllabic words—that almost no one uses in daily conversations. Visualizing situations in which you might need to use some of these words itself is a chore for the imagination, unless you too are planning to write a mind-melting maximalist novel or simply want to add more ammunition to your Scrabble arsenal. “That’s cachexia for 284 points, dude!”

All language learners face the challenge of developing their vocabulary to achieve fluency. It is one thing to know where certain types of words ought to go in a sentence (syntax), but it is another to find the exact words to plug into a sentence in a conversation or other form of communication. Learners often know what they want to say in another language, but they may not know the exact word to help them say it in the target language. A lack of vocabulary often leads to a reliance on circumlocution, or using words we do know to describe the thing or concept we do not know, either as a conversational strategy or a coping mechanism.

Reading is a great way to increase vocabulary. Reading alone is not going to make anyone fluent in all four skill areas (reading, writing, listening, and speaking), but it can provide a rich source of comprehensible input. (Much of Infinite Jest does not even begin to approach what Stephen Krashen would call “i + 12,” let alone “i + 1.”) When learners encounter unknown words in books, articles, or other publications, they can use any number of strategies to bring that word into their personal lexicon.

Reading is a great way to increase vocabulary. Reading alone is not going to make anyone fluent in all four skill areas (reading, writing, listening, and speaking), but it can provide a rich source of comprehensible input. (Much of Infinite Jest does not even begin to approach what Stephen Krashen would call “i + 12,” let alone “i + 1.”) When learners encounter unknown words in books, articles, or other publications, they can use any number of strategies to bring that word into their personal lexicon.

-

-

- Look up the word in a dictionary and read the definition out loud

- Use the immediate context in the passage to make sense of the word

- Write down the word in a notebook as part of a vocabulary list and drill yourself on the word and its meaning

- Use the word in other sentences, either written or spoken, and in other situations or contexts

-

Even individuals who have spoken a language for many years encounter words they do not recognize from time to time. According to a BBC article, a typical “native speaker” only knows about 15,000–20,000 word families, but English contains many more word families or “lemmas” than that. No one can be a master of all domains of linguistic usage, so someone like me with an advanced degree in English will constantly run across new words through reading different types of material. That does not mean we should shoot to hang around the average. Knowing more words than we need to use in our daily personal and professional lives can enrich our worldviews and help us make connections and associations that lead us down new avenues of thought. In short, it makes us well-rounded, broader-minded people.

In this article, I had originally intended to provide my own new vocabulary list—which is something I used to do in my university German courses—based on my own reading of Infinite Jest. The list would consist of words like Kekuléan and presbyopic and espadrilles, as well as numerous drug-related terms. However, I am still compiling that list and may be at it for the foreseeable future. Numerous other people have already compiled their own online Infinite Jest word lists, though, so I am providing links to those resources. Feel free to use them to sate your curiosity, increase your own vocabulary, or at the very least–if you’re at all like me–pad your Scrabble scores.

“Over 200 Words Collected from Infinite Jest” (Rob Hoffman)

“Infinite Jest Vocabulary” (Ben Zimmer)

“What David Foster Wallace Circled in His Dictionary” (Slate)

“Words from Infinite Jest” (Grant Barrett)

“Infinite Jest: David Foster Wallace”

“Words David Foster Wallace Circled in His Dictionary That Were Used in Infinite Jest (And Where They Appear)” (DFW Words)

This post was previously published on our site in 2020 and is appearing here as part of website makeover. ~ Jeff Howard